Chang’e-5: The People Who Helped Drill the Moon

为“嫦娥”助力月壤钻取的人

A behind-the-scenes interview feature about the engineers and researchers who made lunar sampling possible—turning a national mission into a chain of constraints, rehearsals, and decision-making under uncertainty.

Editor’s note

编辑说明

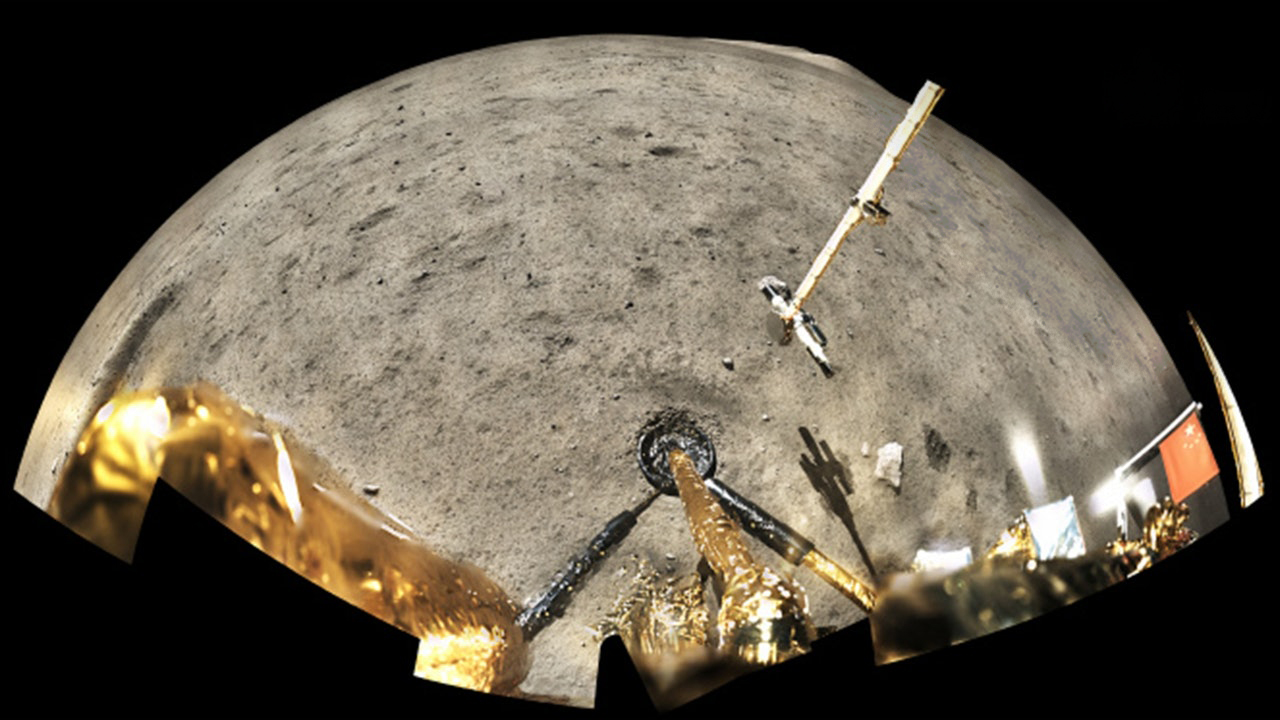

In public memory, Chang’e-5 is often reduced to a single triumphant image: the capsule returning, the dust secured, the mission completed. This piece examines how the Chang’e-5 returned samples reshaped long-standing assumptions in lunar science. Rather than treating the mission as a technological milestone alone, the reporting focuses on how physical samples enable scientists to re-evaluate volcanic history, dating methods, and the Moon’s internal structure.

Key questions

核心问题框架

- How do returned lunar samples recalibrate existing geological models?

- Why does sampling from a younger volcanic region matter?

- What limitations of crater-count dating does Chang’e-5 expose?

- How can physical samples challenge assumptions about the Moon’s dryness and evolution?

Selected excerpts

文章节选

Excerpt 1 · Why Chang’e-5 matters: two lava plains, two very different clocks.

The landing zone of Chang’e-5 covered about 55,000 square kilometers, and within it sat several distinct geological units. One was Mons Rümker, a volcanic dome with a steeper slope—harder, riskier terrain for landing. Another was the relatively flat mare, which can be divided into western and eastern parts. The western mare formed earlier; its estimated age is around 3.4 billion years, shaped by volcanic material that later underwent space weathering and became lunar soil. The eastern mare is younger, with an estimated age of about 1.5 billion years—no earlier than 2 billion. The gap between the two is substantial: at least about 1.5 billion years.

Excerpt 2 · One number that would rewrite a long-standing assumption about lunar volcanism.

Apollo brought back many volcanic rock samples, and none of them dated to younger than three billion years. Based on that, the scientific community concluded that lunar volcanism had ceased before three billion years ago—unlike on Earth, where volcanism remains active even today.

Excerpt 3 · A dating method widely used across planets, waiting for a single calibration point.

There is also the question of dating methods. Is the crater-count chronology used internationally truly reliable? If the age measured from returned samples matches the age derived from crater counting, then crater-count dating can be confirmed. If not, the method needs to be recalibrated. Today, crater counting is used not only for the Moon but also for Mars, yet it still lacks a solid calibration point. If this can be pinned down, it will be significant not just for lunar studies but for research on other worlds as well.

Excerpt 4 · Volatiles: what a “dry Moon” model might have missed.

Another closely related line of research concerns gases and volatiles inside the Moon—water, carbon dioxide, halogens and other substances that become gaseous at high temperatures. In many Moon-formation models, the Moon is thought to contain very little of these, because it went through an extremely high-temperature phase and much of the volatile material escaped. If we can detect volatiles in the roughly 1.5-billion-year-old samples, we can ask: did the products of volcanic activity at that time contain volatile elements? Does the lunar interior hold volatiles at all? On Earth, volcanic eruptions visibly vent gases; here we are trying to trace where such gases would have come from on the Moon.

What this demonstrates

它能证明什么

- Translating planetary science research into accessible narrative reporting

- Using interviews to unpack scientific methods, uncertainty, and model revision

- Connecting returned samples to broader questions of planetary history and knowledge validation